Abstract: This article purports to unfold the structural rules and functional mechanism governing mythical discourse from a semiotic perspective. With insights from three semiotic pioneers, the author attempts to interpret myth within a framework of syntactic, semantic and pragmatic dimensions. Just in this vein, the article strongly advocates that mythical sign ought to be structurally broken into components, which have semantic significations to correspond, and are governed by a set of rules as well.

Key words: mythical discourse; semiotic analysis; syntactic structure; semantic components; pragmatic function

Many myths are developed in the form of a symbolic system. The entities of myth and their mutual relations are mostly represented as a set of metaphysical factors, which cannot be perceptually made sense of within an empirical framework. In other words, the problem of how to understand the true meaning of myths will naturally be correlated with such a basic cognition that myths are some discursive systems, consisting of a variety of anomalous sentences. What such a system designates cannot be interpreted directly from its surface representation. It seems essential to seek its meaning beyond the mythical discourse itself, and thus necessary to resort to a semiotic interpretation. We are therefore in a position to see myth as a typical semiotic system. However, the study of myths from the semiotic viewpoint is by no means identical with the discipline of mythology, despite many interrelations between them.

1. Reflection on the Contributions of the Three Semiotic Pioneers

Before undertaking a semiotic investigation into mythical discourse, we must first of all review different contributions to semiotic theories respectively by Saussure, Peirce and Hjelmslev. There are in fact many characteristics common to the three pioneers for their definitions of sign. All of them think that the nature of a sign consists in its “signifying” or “standing for” function, namely, a sign purports to couple something present with something else absent. It is only through this special function that a communicative act can succeed even without referring to a perceptual entity in a particular circumstance. In this sense, any transmission of knowledge beyond perceptual limitation might be interpreted as a by-product resulting from mankind’s semiotic cognition. It is due to this semiotic function that human beings can compensate for spatial restriction in identifying those distant entities, or for temporal limitation in referring to those historical events. In brief, we can avail ourselves of the limited amount of sign-vehicles available at present to signify a huge repertoire of knowledge, that is, any set of potential things, which are absent in the communicative environment involved.

Nonetheless, despite the fact that Peirce insists on including anything in the range of sign only if it can stand for something else, Saussure merely tends to define those artifacts human intentionally produced as sign. On contrast, those natural phenomena and unintentional products of human beings could not be considered as signs in Saussure’s semiotic definition. On the other hand, Hjelmslev inclines to confine his semiotic topic in the range of natural language.

Be that as it may, it should be indicated that a thing is not capable of automatically signifying something else. The relation of a sign-vehicle to the corresponding content has to be identified by an agent who is participating in the semiosis of sign, and accepted unanimously by a particular cultural community. In this vein, the semiotic act in interpreting the relation of one entity or item to another is free and bound simultaneously. An interpreter can arbitrarily assign certain semiotic relevancy to some things even though there is not any objective connection between these things. This is the case particularly with the symbol signs. Obviously, we can find some physical relation or some other types of relevancy between a lot of things, which are therefore classified into either icon or index, as elaborated in Peirce’s work. But the situation for symbol is radically different. When some arbitrary relation is assigned to the things which are symbols in semiotic terms, such a kind of relation must be conventionalized by human beings throughout the process of signification.

Peirce indicates that sign is “something which stands to somebody for something in some respects or capacity” (Peirce: 1958, p.228). He treats a sign not as a bi-fold entity, just like Saussure, but as a tri-fold one, namely, “something A”, “something B” (for convenience of explanation, we tentatively label these two kinds of “something” respectively as A and B), and “respects or capacity”. The third factor—“respects or capacity”—is also termed “interpretant”. Even though a lot of ambiguities indeed underlie this term, it may be most appropriately understood as representing an intermediary factor to facilitate a semiosis. Peirce has clearly expressed his argument in this connection: “By the semiosis I mean an action, an influence, which is, or involves, a cooperation of three subjects, such as a sign, its objects and its interpretant, this tri-relation influence not being in any way resolvable into actions between pairs.’(op. cit. p.484)

Peirce’s approach to sign apparently suggests a kind of dynamic style. It appears that semiotic investigation ought not to be confined in the study of what meanings will intuitively correspond to its vehicle. Semiotics should prefer an interpretive approach to a descriptive one; in other words, it should interpret the potentiality for relating some thing to something else, rather than describe the semiotic relation as a fait accompli. It should answer the question of how “something A” is related to “something B”. In this sense, semiotics is an interpretive rather than a descriptive science.

On the contrary, Saussure defines sign as a bi-fold entity, which is composed of “significant” and “significé”. There exists a direct relationship between the “significant” and “significé” without any intermediate dimension, such as Peirce’s “interpretant”. Saussure has also stressed that “signifie” is not simply equivalent to any perceptual object, but rather serves as a psychological image of this object. This understanding of the content of sign is apparently different from what was defined in Peirce’s work.

Hjelmslev’s contribution to semiotics consists in his hierarchical view of sign. He is not content with Saussure’s simple division of a sign into two sides, such as “significant” and “significé”, but rather likes to further divide them into several levels, respectively with their distinct semiotic characteristics. He replaces Saussure’s “significant” and “significé” respectively with “expression” and “content”, and assigns a structural description to them. According to him, both the plane of “expression” and that of ‘content’ can be further analyzed into theoretically endless sub-levels. His idea of semiotic hierarchy can be diagrammed as below:

|

|

|

etc. |

etc. |

|||

|

|

expression |

content |

||||

|

expression |

content |

|||||

|

content |

expression |

|

||||

|

etc. |

etc. |

|

|

|||

The scholarly legacy of the three pioneers will be helpful for us to understand the nature of sign, and its structural characteristics. We may outline some theoretical principles that regulate our later study of mythical sign, on the ground of the pioneers’ findings.

A. Semiotics of myth must provide a rational classification of mythical signs.

a) A method of classification based on the source of signs has been advocated in Sebeok’s work (Sebeok: 1991).

b) There is also a method of sign classification based on the medium by which mythical sign is conveyed. It is typically to differentiate mythical discourse from mythical ritual on the ground that mythical discourse is conveyed with natural language, whereas mythical ritual is performed in a behavioral mode.

c) There is a method of classification based on the narrative theme, which characterizes mythical discourse. Such a kind of theme fulfills the function of mythical motif, and at the same time, serves as the most important factor of mythical sign, because mythical discourse as a whole is always developed structurally around the theme.

d) There is possibly a method of classification based on a statistical criterion. This is the case with those quantitative distinctions. For example, we may differentiate discretely individual entities of mythical sign from their combination, namely, an episode, or entire discourse of myth. In this vein, the discretely individual entities can be understood as structurally simple signs, whereas a mythical episode or the whole discourse of myth can be interpreted as structurally complex signs. We may find some extreme situations in the content of these signs: some narrative meanings an entire sign discourse possesses cannot be found in the discretely individual signs.

e) There is possibly a method of classification based on the interpretant of sign. Because the interpretant can be utilized to explain the rules for combining the side of ‘signifiant’ with that of ‘signifié’, or in other words, the plane of expression and that of content, we can interpret Peircean tri-classes of signs, i.e. icon, index and symbol, as a result governed by a set of rules: similarity, contiguity and convention.

B. Semiotics of myth should describe the syntactic rules inherent in the expression plane of myth.

a) Such syntactic rules should govern combination of the discretely individual signs of myth.

b) Such syntactic rules should provide a possibility for analyzing an individual sign into some components.

C. A semiotics of myth should provide a system of syntactic or semantic markers to categorize or subcategorize a mythical sign.

a) Such a system of semantic markers should describe not merely denotative components of meaning, but also those connotative shades, which result from the contextual restriction involved;

b) Such a system of semantic markers should also provide us an opportunity to semantically compare some individual mythical signs with others. Only after this comparison is made, may we be able to fix semantic relations between them; for example, perhaps, we may find the relations of synonymy, antonym or hyponymy between them.

2. Syntactic, Semantic and Pragmatic Dimensions

A syntactic approach entails that we should treat a discourse of myth structurally either as a whole configuration, or as a coherently hierarchical system, which is constituted of segments of a discursive utterance. Such a structural segmentation of the mythical discourse is based on natural paragraphs, or in other words, on some episodes of the particular discourse, and even some linguistic sentences and words, if it is represented by means of natural language. And the semantic representation of mythical discourse should at the same time correspond appropriately to the structural segmentation. Be that as it may, structural analysis and semantic interpretation are by no means simply equivalent to the linguistic effort in these dimensions. Many sentences of mythical discourse merely convey the meanings particular to the discourse of a mythical character or style. A linguist, who takes everyday language into account, might have no hesitation to dispose of them rightly as unacceptable linguistic phenomena, or explicit violations of syntactic and semantic rules for natural language. Selection restriction imposed on the combination of linguistic units within a meaningful linguistic sentence is such a typical rule.

In fact, some pragmatic factors, such as sender or narrator, and address or hearer, or reader, of a particular mythical discourse, always determine how to organize the discrete units of this discourse into a systematic whole, and further how to interpret the meanings of such units. When many narrators are in a position to narrate a common theme of myth, they would perhaps organize all the entities of this discourse in so different a structural mode that a variety of radically distinct syntactic combinations might be produced immediately. With regard to the addressee or reader of a mythical discourse, the per-locution responses of the addressees can to a great extent influence semantic interpretation of the particular mythical discourse. Interpretation of the meaning of a myth is often discrepant between addressees who are from different societies or times. Some subjective factors might lead to interpretation of the appraisive function of this myth in a negative or a positive way. This is the case with different opinions on the same dramatics personae and his action. For example, Zeus in the Greek myth might be evaluated as dissolute, or otherwise abundant in emotion, if with different principles of evaluation. Hence a different semantic representation will perhaps be assigned to the same mythical entity.

In summary, the different functions three dimensions have fulfilled, and characteristics they are respectively possessing, can be tentatively elaborated as below:

A. Pragmatic dimension will be concerned with the roles that are performed by the sender and addressee of a mythical sign when they are participating in the communication of a mythical discourse.

a) Sender undertakes to perform some illocutionary acts in conveying a message of mythical utterance;

b) Sender undertakes to employ particular arrangement of the units of mythical discourse in order to express his narrative intent. This function is trespassing the syntactic threshold of mythical signs;

c) Addressee undertakes to meet exactly the requirement of illocutionary acts the sender performed;

d) Addressee undertakes to decode the structural characteristics of mythical discourses sent by the sender and their conventional meanings, in order to understand the sender’s intention. This function will trespass the thresholds of both syntax and semantics relevant to mythical discourses.

B. Syntactic dimension will be concerned with the rules for combining the structural units of mythical sign.

a) It considers not only the structural interrelation between the signs, but also the grammatical acceptability for the structural combination of these sign units, which will depend on the cultural framework of a particular mythical community. The combinatory mode in arranging these sign units varies from one mythical community to another. The cultural factor of this dimension determines that it would trespass the pragmatic threshold.

b) It also needs to consider those restrictions upon the structurally combinatory possibility of semantic markers for mythical entities, which is simultaneously trespassing the threshold of semantic dimension.

C. Semantic dimension needs to take into account the ‘signifié’ of mythical sign, and the rules for coupling a sign –vehicle with its content.

a) It must consider the fact that some meaning components are incompatible to the combination laws underlying the mythical signs; here, it also trespasses the threshold of syntax.

b) Even some behavioral response, or emotive factors, or moral evaluation, should also be incorporated into the semantic domain of the particular mythical sign. In this sense, it simultaneously trespasses the threshold of pragmatic dimension.

c) Except for the semantic components of discrete units of mythical sign, a system of semantic features for the mythical text as a whole should also be taken into account. In other words, the semantic dimension must appropriately specify the problem of whether a particular mythical discourse is designative, prescriptive, or appraisive in its signifying mode. Here, it trespasses the threshold of pragmatic dimension.

d) Sometimes, a discourse of myth can be understood as resulting from a narrative enhancement of the most important unit of this mythical sign. For example, the myths having “flood”, “sky”, “earth”, “sellar nebula” and so on as their motifs are always represented as narrative enlargement of the motifs with both semantic characteristics and syntactic combinations. In this sense, it trespasses the threshold of syntactic dimension.

3. Typology of Mythical Signs

A typology of mythical signs will vary with different criteria. Thus, we may be confronted with a complex situation, in which a sign has a good reason to belong to different classes. We will take such a situation into account on the ground that a crisis-cross classification of the same sign may be beneficial to our understanding of its multiple functions. However, to take a typological approach entails a structural segmentation of the mythical discourse involved. Thus, some statistical criteria seem to be suitable for exposition.

On the other hand, it should be specified that the elements of a mythical discourse sometimes refer to entities, sometimes events, or even situations on the condition of whether the element is a discretely individual sign, such as the word-like unit, or a complex sign, such as the sentence-like unit, and even the whole discourse of myth. If a word-like sign is merely capable of denoting an entity, the structurally complex signs, such as those in a sentence-like unit or a whole discourse, should be understood as the signs of denoting both the entity and the events or situations.

Be that as it may, these units of signs are often interactive in a great degree. A word-like sign is actually not capable of denoting any mythical entity unless put in the framework of a discourse of myth. Thus, some individual signs, such as a flood, a species of animal or plant, and a stellar system, can not denote anything beyond the range of perceptual world, unless they appear in a mythical discourse. In other words, it is the mythical style that gives rise to a situation, in which the individual signs finally enrich their semantic components with particularities of the mythical world. A flood may signify a metaphysical thing which is able to destroy vicious people but simultaneously makes some preferential persons rescued in an indiscernible time. Likewise, a species of animal or plant can be interpreted as an ancestor in a particular society. Moreover, an individual mythical sign will acquire some semantic properties when put in a sentence-like sign unit, where it is capable of establishing a syntactic relation to other signs. As to the sentence-like mythical signs, we can also indicate that they will inevitably be attributed to ungrammatical selections, which apparently violate the rules of natural language. Only if put in a mythical discourse could these anomalous signs become normal for expressing metaphysical or mythical meaning. Thus, a sentence-like sign, such as “colorless green ideas sleeps furiously”, will become acceptable if in the framework of myth. In other words, it is the myth that makes grammatical restriction, for example, the rule of selective restriction in natural language less restricted that it is meaningful in a style of mythical component. On the other hand, a mythical discourse as a whole, can not exhibit its particular mythical features unless structurally composed of these individual signs.

The relation of myth to natural language is so intense that a semiotic approach to the structure of mythical signs is inevitably susceptible to the influence of linguistics. In this connection, a study of the “significant” of a mythical sign is liable to be transformed into investigation of the grammatical rules. Likewise, a study of the “signifié” of a mythical sign will often be transformed into the research in the semantic pattern of a word, a sentence, or a discourse, and further represented as a proposition, a plot, or even a story.

Even though the mythical signs are in general represented by means of linguistic expressions, as elucidated above, it will run a great risk to absolutely mix them or replace the study of the structure of myth with linguistics. The point at issue is that we must discriminate structural analysis of mythical signs from that of natural language. For instance, as to the analysis of the word-like mythical signs, we need not to consider their morphological rules, although it is an integral part to linguistics. Likewise, as to the analysis of sentence-like mythical signs, we need not to discuss those grammatical elements, which only function to make other linguistic components complete in grammatical relation. With regard to the analysis of a whole discourse of myth, we need not to draw much attention to those writing techniques.

Therefore, we feel necessary to take another angle for classifying mythical signs. If the word-like mythical signs are denoted with the term of individual signs, those resulting from the combination of these individual signs should be classified into textual signs. Even the textual signs can further be sub-classified into the classes of micro-textual and macro-textual signs. The micro-textual sign includes the sentence-like unit of signs, whereas the macro-textual one only refers to a whole discourse of myth.

It is indeed true that a textual sign is structurally composed of a variety of individual signs. However, the textual sign should be represented as a kind of systematically coherent structure rather than an arithmetic sum of the individual items. Although it has to structurally depend on discretely individual signs for signifying some mythical event or situation, the textual sign still performs some particular function beyond simple combination of the individual signs. In other words, the textual sign has some special textual meanings.

Nevertheless, how to define this textual meaning would remain a puzzling problem if we confine ourselves merely within a text. On the contrary, we often find that the function of a text is defined by means of a comparison with others; in other words, only if in a relation to other systems, can it define its functional position. In fact, the problem of whether a mythical discourse is in function designative, appraisive, or prescriptive, has to be determined on the ground of a detailed comparison between different discourses.

As Lévi-Strauss has elucidated, a system is by no means equal to the mechanical summation of their components. “That arrangement alone is structured which meets two conditions: that it be a system, ruled by an internal cohesiveness; and this cohesiveness, inaccessible to observation in an isolated system, we revealed in the study of transformation, through which the similar properties in apparently different systems are brought to light”(Lévi-Strauss:1963,p.38)

As to the micro-textual signs in sentence-like unit, we should specify that some signs in fact possess different truth-values because of their different reference worlds, namely either a mythical world or an empirical one. It is obvious that a radical difference exists between a linguistic sign and a mythical one. The former utilizes everyday language, and thus refers to an empirical world, while the latter makes use of mythical language, and thus denotes a metaphysical world.

At the same time, we must emphasize that some judgments drawn from the propositions of sentence-like mythical signs are actually recognized first, and conventionally accepted finally by some particular mythical community. In this sense, these judgments are essentially semiotic, which are apparently different from those factual judgments majorly based on the contingent facts involved. However, from the ontological point of view, even these semiotic judgments are based on a personal observation of some accidental facts. Since this kind of observation is often practiced by some people who have a higher political position in the mythical community, his judgments of these contingent facts are usually prescriptively admitted by all the members of the mythical community. Thus a semiotic judgment proceeds in a close relation to the factual one. Therefore, when we take into account the structural rules for determining function, or semantic pattern of a sign, we should pay much attention to this issue.

With regard to a group of sentence-like mythical signs, namely episodes of mythical discourse, we cannot but specify that this kind of micro-textual signs are in function dependent upon both their immediate constituents, such as a set of sentence-like signs, and those other episodes co-existing with them in the same discourse. A systematic concatenation of the sentence-like units will undoubtedly contribute much to the textual meaning formation of a complete episode, whereas structural coherence of an episode has to be generally interpreted in reference to other episodes of the discourse. Distinguished from isolated sentences, an episode can refer to sequence of acts, set of facts or situations, and furthermore some plots.

As to the whole discourse, we should identify a certain narrative style, which is merely suggested by the discourse as a whole. The stylistic features for a particular discourse of myth will help us differentiate it from other mythical discourse. When we attempt to take into account the inner structure of this macro-textual sign in reference to their semantic dimension, we should indicate that some mythical themes or motifs are determined only if in reference to the framework of discourse as a whole. The discipline of mythology is just proceeding on the ground of such mythical themes to give an appropriate classification of many myth variations in the world.

However, it is necessary to add that some factors of semantic dimension, in other words, those signified meanings, are almost universal to every macro-textual sign. We will see that many mythical discourses share some common mythemes, although they are radically different in structural arrangement of discursive constituents. This is the reason why we tend to deal with a variety of discourses under a common topic. In brief, we can immediately find that some macro-textual discourses are myths rather than historical anecdotes or literary writings in view of their particular mythical motifs.

We will adduce some examples of mythical discourses to illustrate our view on the problem of mythical structure and function.

4. Two Myths as Example

Myth 1

I am the Eternal Spirit,

I am the sun that rose from the Primeval Waters.

My soul is God, I am the creator of the Word.

Evil is my abomination, I see it not.

I am the Word, which will never be annihilated

in this my name of ‘soul’.

The Word came into being.

All things were mine when I was alone.

I was Re in [all] his first manifestations:

I was the great one who came into being of himself,

Who created all his names as the Companies of the [lesser]

Gods,

he who is irresistible among the gods.

The battleship of the gods was made according to what I said.

Now I know the name of the great god who was therein.

I was that great

Who looks after the decision of all that is.

I fulfilled all my desires when I was alone,

Before there had appeared a second to be with me in this place;

I assumed form as that great soul wherein I started being creative

While still in the Primeval Waters in a state of inertness,

Before I had found anywhere to stand.

I considered in my heart, I planned in my head how I should make every shape

——this was while I was still alone——I planned in my heart how I should create

Other beings——the myriad forms of Khopri——and that there should come into being their children and theirs.

So it was I who spat forth Shu and expectorated Tefnut

so that where there had been one god there were now three as well as myself

and there were now a male and a female in the world.

Shu and Tefnut rejoiced there in the Primeval Waters in which

they were.

After an age my Eye brought them to me and they approached me

And joined my body, that they might issue from me.

When I rubbed with my fist my heart came into my mouth in that

I spat forth Shu and expectorated Tefnut.

But, as my father was relaxed…aged…serpents…

I wept tears: the form of my Eye; and that is how mankind came into existence.

I replaced it with a shining one [the sun] and it became enraged with me when it came back and found another growing in its place.

(Egyptian myth, cited from Leeming, D: 1990, pp.17-18)

Myth 2

1. Then even nothingness was not, nor existence. There was no air then, nor the heavens beyond it. What covered it? Where was it? In whose keeping? Was there then cosmic water, in depth unfathomed?

2. Then there were neither death nor immortality, nor was there then the torch of night and day. The One breathed windlessly and self-sustaining. There was that One then, and there was no other.

3. At first there was only darkness wrapped in darkness. All this was only unillumined water. That One which came to be, enclosed in nothing, arose at last, born of the power of heat.

4. In the beginning desire descended on it—— that was the primal seed, born of the mind. That sages who have searched their hearts with wisdom know that which is, is kin to that which is not.

5. And they have stretched their cord across the void, and know what was above, and what below. Seminal powers made fertile mighty forces. Below was strength, and over it was impulse.

6. But, after all, who knows, and who can say whence it all came, and how creation happened? The gods themselves are later than creation, so who knows truly whence it has arisen?

7. Whence all creation had its origin, he, whether he fashioned it or whether he did not, he, who surveys it all from highest heaven, he knows——or maybe even he does not know.

(Indian myth, op.cit. pp. 29-30)

Both the examples are narrated in a poetic style. However, the example 1 represents the narrative mode of direct quotation, whereas the example 2, that of indirect quotation. The example 1 as a whole discourse is composed of three episodes, yet the example 2, seven episodes. The episodes as micro-textual signs in the example 1 take a variety of declarative sentence as their immediate constituents. In contrast, the episodes of the example 2 take some sentences of question-answer type as their immediate constituents. Thus, the speech acts performed in terms of the episodes, are obviously different for these two examples. An apparent difference between some grammatical categories can also be found in them. In this connection, the example 1 is mainly expressed by means of the first person category, but the example 2, the third person category. Although these two examples are different in respect of the factors of the expressive plane, we can still find some similarities in their content plane, especially at the macro-textual level. In brief, both these two examples have the motif of “creation of universe” in common, which makes one classify them into same mythical type, although they are narrated by virtue of different devices in different territories. However, we should bear in mind that the examples 1 and 2 are by no means equivalent in respect of the content plane. We will attempt to factorize this motif into multiple sub-codes. Thus, the planes of both expression and content will be respectively denoted with ‘Sa’ and ‘Sé’. Except for this, some other terms should also be introduced into structural description of them.

First, the concept of “contextual restriction” (cons) and “circumstantial restriction” (cirs) should be given a consideration. The former refers to the discursive context, in which individual and micro-textual signs co-exist. The latter denotes those extra-discursive factors, such as cultural conventions particular to some mythical communities, and those epistemological features of the mythical world. The semantic impact from either the discursive restriction or extra-discursive one can be discerned almost at every level of the mythical discourses.

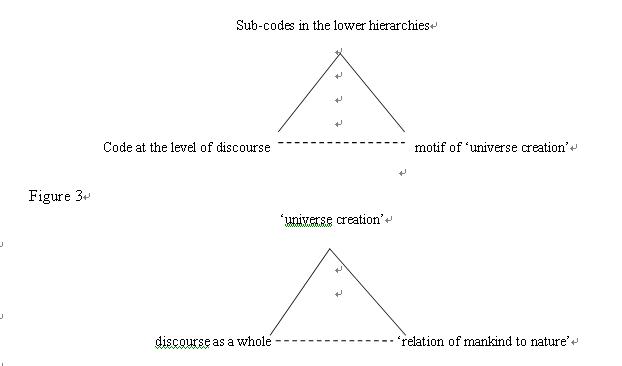

Second, the semantic structure of these two examples should further be divided into the class of denotative features and that of connotative ones, on the ground of whether the semantic features posit any other features as their mediation. We will draw the distinction between them according to Eco’s theoretical principle. Eco has indicated that “a denotative marker is one of the positions within a semantic system to which the code makes a sign-vehicle correspond through the mediation of a preceding denotative marker, thus establishing a correlation between a sign-function and a new semantic unit.”(Eco: 1976, p.85) The close correlation between a denotative semantic marker and a connotative one can sufficiently be illustrated by means of the semantic configurations seen in different hierarchies of signification. From the semantic marker of “universe creation” we can further obtain a connotative semantic content, such as “relation of mankind to nature”. It is just through mediation of the former that we discover the underlined semantic content of “relation of mankind to nature”.

Third, some semantic markers of the lower hierarchies, such as those at the levels of individual signs, and micro-textual ones, can shed some light on the semantic configuration of the higher hierarchy, such as the level of macro-textual discourse. So is the case vice versa. In fact, the structural hierarchies become mutually explanatory in their semantic configurations. In this sense, any one side of them can be said to represent their interpretative function in terms of “interpretant”. For instance, the semantic marker of “universe creation” at the level of whole discourse will be explained on the ground of individual signs, such as ‘the Creator of the Order’, ‘rising from the Primeval Water’ and so on. These individual signs actually serve as factors pertinent to the semantic feature of “universe creation” at the macro——textual level. In this vein, the interpretant is also represented as a mediation of the semantic path leading to the target marker of meaning. At the same time, the denotative semantic features also function as an interpretant to make the connotative markers possible, if considered from the mediation effect. We thus have a good reason to outline the correlations between these dimensions by virtue of a set of triangles in analogy to what have been advocated by Ogden & Richards. (Ogden & Richards, 1923)

These figures might be taken to represent the paths of the semantic configuration for the examples 1 and 2.

On the other hand, we often find that any change in the expressive elements on the Sa plane will lead to a change on the Sé plane, and semantic pattern of a particular mythical sign might be altered finally. Hence a new correspondence between Sa and Sé. As to the two examples, we may thus assume that the two discourses of myth are possibly narrated at first in a mode of prose, and finally represented in a poetic style. The authors of these discourses invent the current poetic form to convey their particular intents. In other words, the expressive form of prose has been transformed into the present poetic form by some unidentified narrators in an indiscernible time. Thus, a new code is invented.

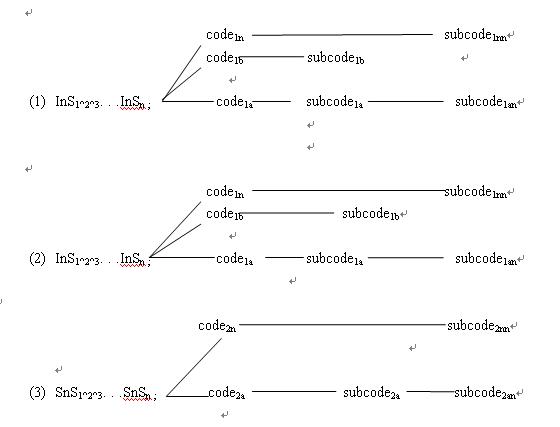

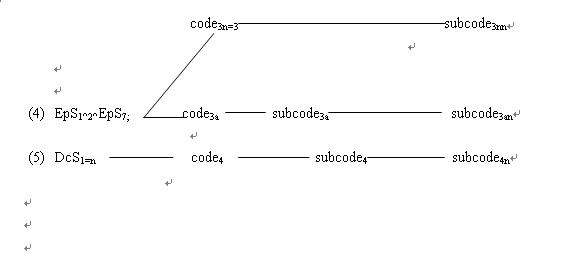

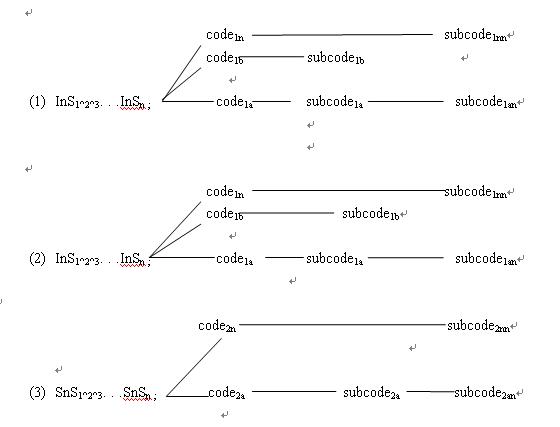

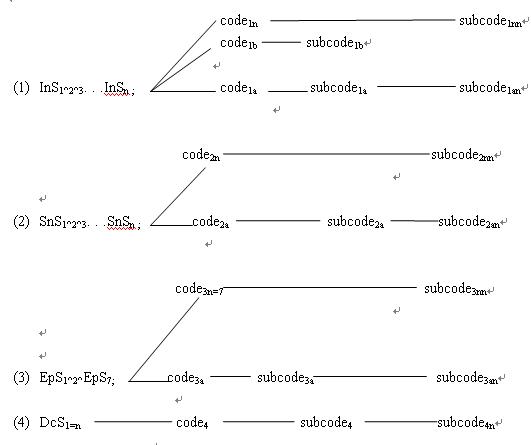

Here, we will further outline the structural configurations the two examples respectively possess on the ground of the theoretical principles elaborated above. First of all, we will enumerate the abbreviations of terms as follows:

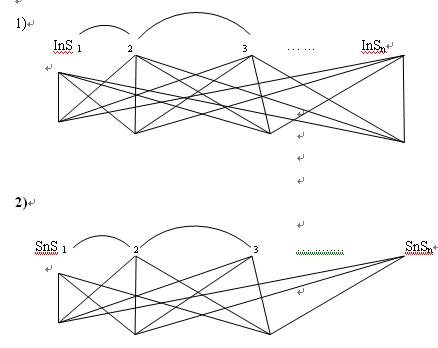

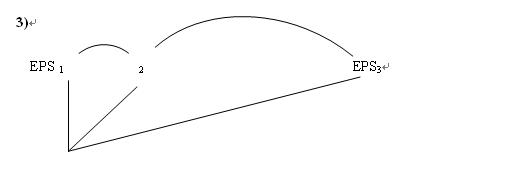

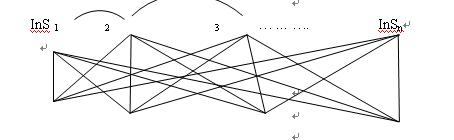

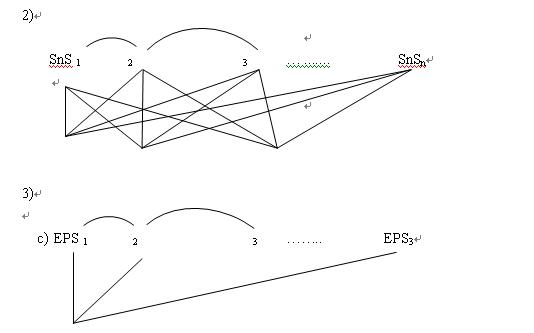

1) A stratified view of the discourse requires that the two discourse be structurally segmented into four hierarchies, denoted by the serial numbers from 1) to 4).They respectively represent individual signs in word-like unit, micro-textual signs in both sentence-like and episode-like unit, and the macro-textual signs at the level of whole discourse.

2) The mark “^” represents the concatenation relation between the adjacent elements at every level.

3) DcS= discursive signs; EpS= episode-like signs; SnS= sentence-like signs; InS= individual signs in a word-like unit; d= denotative semantic marker; c=connotative semantic marker; cont = contextual restriction; cirs= circumstantial restriction; NP= noun phrase; VP= verb phrase; rheP= rhetorical personification; anim= animate; hum= human; S= sentence; prop= proposition; metap= metaphysical’; epis= epistemological; inst= instrumentality; En= event; sin=singular; plu= plural; inter= interrogative; UniverC= universe creation. Re= relation of mankind to nature.

Thus we can represent the structural configurations of the two examples in respect of their expression and content planes as below.

Figure 1

The structural configuration of Example1 on expression plane

Table 2

The structural configuration of Example 2 on expression plane

Table 3

The structural configuration of Example 1 on content plane

Figure 4

The structural configuration of Example 2 on content plane

Of course, we can explain the relation of Sa to Sé, or in other words, the correspondence of expression plane to the content level from another point of view. A code theory requires that a sign be understood from the correlation of these two planes. The correspondence between these two planes will thus inevitably result in a new code. The concept of code entails a kind of semiotic practice, which makes a sign complete in both form and meaning. Since we have already analyzed the situation where an expressive plane corresponds to a content level, it seems plausible to transform the above figures into several diagrams of code structure. Thus, the figures 3 and 4 can be rephrased in terms of codes. It is the signs of different hierarchies that bring about a variety of codes through coupling sign units with denotative and connotative semantic markers. The quantity of codes and sub-codes will help us statistically estimate the frequency of semiotic practice in every hierarchy, although such an approach needs much elaboration, which is beyond our present scope of discussion. At the same time, it worth noting that figures 5 and 6 are in nature the substitutive forms of figures 3 and 4 from the angle of semiotic practice. The codes and sub-codes in the below diagrams have in fact reflected different extents to which functional statuses of the signification elements were evaluated through a lot of subscripts.

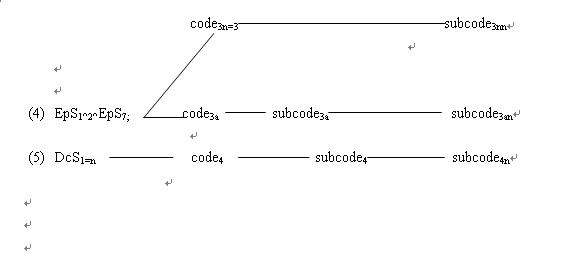

Figure 5

Code structure of Example 1

Figure 6

Code structure of Example 2

These models have provided a good opportunity for us to come to the following conclusions:

1) The models have suggested that the example 1 and 2 are partially isomorphic because of their similar structure pattern in code-making. But there exist a lot of differences between the examples in respect of the values of codes and sub-codes.

2) While the codes are the superordinate items relative to the sub-codes, the sub-codes are conversely in a hyponymic relation to them. On the other hand, the codes in the lower hierarchies are also in a hyponymic relation to those codes in the higher planes. This is dependent on the stratified character the expressive planes respectively have.

3) The codes are polysemous because of their multiple sub-codes generated. Even the sub-codes too are polysemous in view of other sub-codes they generated in turn.

4) Both codes and sub-codes in one hierarchy seem synonymous to those of other hierarchies, since they have some semantic features in common.

5) There are some over-codes inherent in the two types of discourse. The stylistic difference between them is undoubtedly due to those distinct over-codes used in weaving the structure of mythical discourse, as seen in different sentence types, for example, “assertive” in the example 1 and “interrogative” in the example 2.

Reference

Austin, J. L. (1962): How to do Things with Words,

Benveniste, E. (1966): Problems de Linguistique Generale, Gallimard: Press

Chomsky, N. (1957): Syntactic Structures, Mouton:

Eco, U. (1976): A Theory of Semiotics,

Hjelmslev, J. (1961): Prolegomena to a Theory of Language, University of

Hymes, D. (1971): “The wife who goes out like a man: reinterpretation of a Clackamas Chinook myth”, in Maranda, P. & Maranda, K. ed. Structural Analysis of Oral Tradition,

Jakobson, R. (1990): On Language,

Levi-Strauss, C. (1963): Structural Anthropology, Basic Books:

Liszka J. (1989): The semiotic of Myth,

Leeming, J. L. (1990): The World of Myth,

Ogden & Richards (1923): The Meaning of Meaning, Routledge & Kegan Plaul:

Peirce, S. (1958): Collected Papers,

Saussure, F. de. (1983): Course in General Linguistics. Eds. Charles Bally and Albert Sechehaye. Trans. Roy Harris.

Sebeok, A. T. (1991): A Sign is just a Sign,

(Lu De-ping, Ph.D. Professor of China Youth University for Political Sciences. His main research interests include traditional semiotic theories, youth culture, mythical semiotics, Saussurean linguistic theory)